Anthèmes refers to two related compositions for violin by French composer Pierre Boulez: Anthèmes I and Anthèmes II.

Anthèmes I is a short piece (c. 9 minutes) for solo violin, commissioned by the 1991 Yehudi Menuhin Violin Competition, and dedicated to Universal Edition’s director Alfred Schlee for his 90th birthday. In 1994, Boulez revised and expanded Anthèmes I into a version for violin and live electronics at IRCAM, resulting in Anthèmes II (c. 18 minutes duration), produced in 1997. (Expansion and revision of earlier works is common in Boulez’s compositional process; see also Structures.)

The title is a hybrid of the French “thèmes” (themes) and the English “anthem”. It is also a play on words with ‘anti-thematicism ‘: “Anthèmes” reunites the “anti” with the “thematic”, and demonstrates Boulez’s re-acceptance of (loose) thematicism following a long period of staunch opposition to it (Goldman 2001, 116–17).

Anthèmes I owes its structure to inspiration Boulez drew from childhood memories of Lent-time Catholic church services, in which the (acrostic) verses of the Jeremiah Lamentations were intoned: Hebrew letters enumerating the verses, and the verses themselves in Latin. Boulez creates two similarly distinct sonic worlds in the work: the Hebrew enumerations become long static or gliding harmonic tones, and the Latin verses become sections that are contrasting action-packed and articulated (though Boulez says that the piece bears no reference to the content of the verses, and takes as its basis solely the idea of two contrasting sonic language-worlds) (Goldman 2001, 119). The piece begins with a seven-tone motive, and trill on the note D: these are the fundamental motives used in its composition. It is also in seven sections: a short introduction, followed by six “verses”, each “verse” preceded by a harmonic-tone “enumeration”. The last section is the longest, culminating in a dialogue between four distinct “characters”, and the piece closes with the two “languages” gradually melding into one as the intervals finally center around the note D and close into a trill, and then a single harmonic. A final “col legno battuto” ends the piece in Boulez’s characteristic witty humour, a gesture of “That’s enough for now! See you later!” (Goldman 2001, 83, 118). [from wikipedia]

See also: Goldman, Jonathan. “Analyzing Pierre Boulez’s Anthèmes: ‘Creating a Labyrinth out of Another Labyrinth’“. Unpublished essay. [Montréal]: Université de Montréal, 2001. OCLC: 48831192.

Andrew Gerzso has for many years been the composer’s chief collaborator on works involving live electronics and the two men regularly discuss their work together. He describes the way in which all the nuances in this nucleus of works were examined in the studio in order to find out which elements could be electronically processed and differentiated. As a result, the process of expanding these works is based not only on abstract structural considerations (such as the questions as to how it may be possible to use electronic procedures to spatialize and to merge or separate specific complexes of sound),but also on concrete considerations bound up with performing practice: in a word, on the way in which the instrument’s technical possibilities may be developed along figurative lines.

IMHO, it is quite clear that the electroacoustic is limited to “dress” the instrumental part, albeit with effects well made. Anthème II is not a real electroacoustic composition and even a revision of the original. But it’s really helpful to students. See also this good page from IRCAM and this one with Max patches.

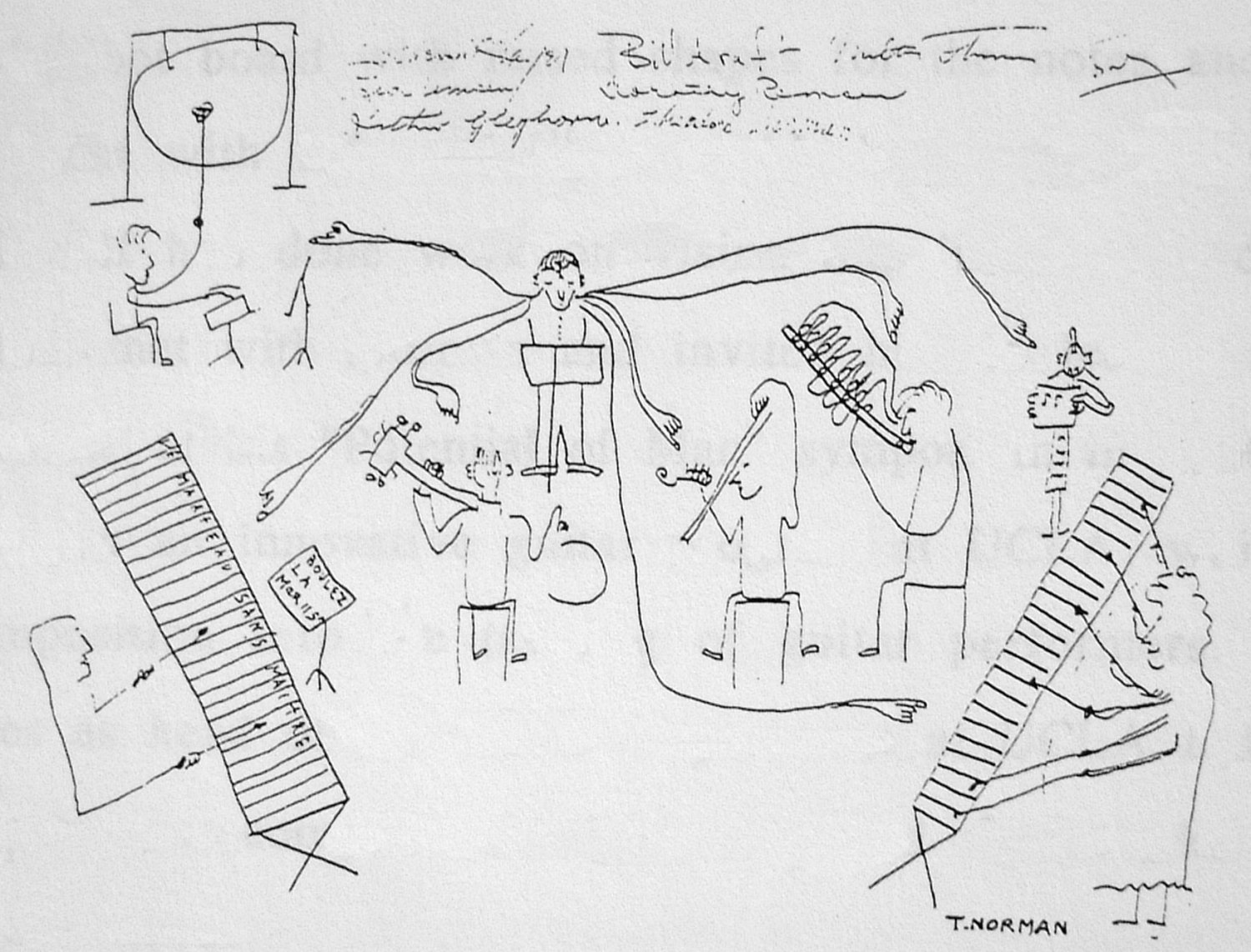

From You Tube, Anthèmes before and after